According to AMI, mechanical recycling in Europe exceeded 8 million tonnes in 2021, with an overall recycling rate of 23.1%, as feedstock insecurities exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic continue.

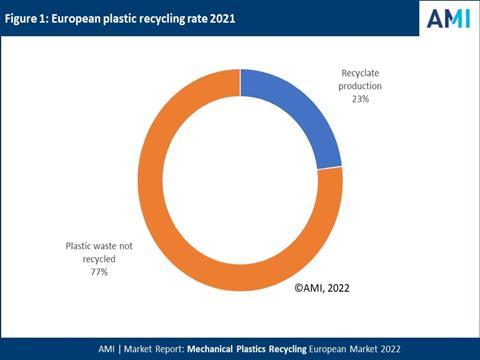

In 2021, AMI says that plastics recyclate production was 8.2 million tonnes, with an annual growth rate of 5.6% predicted up until 2030. Based on an estimated 35.6 million tonnes of commodity plastic entering waste streams in 2021, this figure implies that Europe achieved an overall plastic recycling rate of 23.1%.

AMI reports that most plastic waste is either not collected for recycling or ‘lost’ during the sorting stage, which means it ends up incinerated or in landfill. The group therefore cautions that feedstock is a “finite resource, characterised by bail price fluctuations and variable quality and supply”.

The report identifies the COVID-19 pandemic as a key challenge. During initial lockdowns, the volume of waste being collected for recycling dropped, while demand for recyclate also fell as companies had to close or limit production. However, as economies rebounded, so too has demand for recycled content, especially as EU legislation will require some segments, such as beverage bottles, to have 30% recycled content by 2030.

While AMI acknowledges that the plastics industry appears to be “bouncing back”, challenges associated with COVID-19 remain, with varying effects across the value chain.

The availability of feedstock, as noted by AMI, could present an on-going issue. Writing for Packaging Europe in December 2021, Mark Victory, senior editor of recycling at ICIS, warned of bale supply shortages due to a range of factors, including insufficient collection and sorting capacity, disruptions at recycling facilities due to delayed maintenance and social distancing, and changes to waste input from consumers linked with home working.

Another factor is rising contamination levels, with Victory claiming that some countries saw a 5-7% rise in PCB contamination in 2021. Alongside this, yields are dropping, which will require recyclers to “buy twice the number of bales to get the same value of usable material compared to just a few years ago,” according to Victory.

Companies across the value chain have responded to this challenge with partnerships aimed at securing the supply of feedstock. For example, in December last year, Trinseo entered a definitive agreement to acquire the plastics recycling and converting company Heathland BV – a move intended to ensure a “reliable source” of recycled feedstock.

However, price hikes continue, with ICIS pointing to “record highs” for materials including rPET at the start of 2022. On top of escalating prices for raw materials, gas and oil prices continue to fluctuate, and debates have arisen over where in the value chain this should be absorbed. Ron Marsh from the Polymers for Europe Alliance last year said that “the plastics conversion sector is vulnerable”, with profit margins narrowing and the risk of further production shut-downs lingering.

Experts generally agree that the long-term impacts of COVID-19 and supply chain tensions are difficult to predict, and there is some debate as to how shortages and price hikes will play out for the plastics recycling industry. There is further uncertainty as the European Commission is slated to make updates to legislation including the EU Packaging and Packaging Waste Direction (PPWD), which could influence demand for recycled content. On this note, Nicholas Hodac, director general at UNESDA Soft Drinks Europe, told Packaging Europe: “We’re hopeful for a piece of legislation which will address this situation, and then help us to very quickly correct this imbalance.”

As for other predictions, within the 2030 timeframe of the report, AMI expects to see “additional absorption of recyclate volumes into applications that to date absorb negligible levels” as uses for recyclate become more diverse, offering higher added value. The group also predicts the commercialisation and scaling of production for food-grade rPP and rPS by 2030, with the potential of creating a closed loop system similar to rPET.

There have already been some developments in advancing the mechanical recycling of PS, with Styrenics Circular Solutions (SCS) having recently submitted another application for approval by the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), in this case for its super-cleaning technology by Gneuss. This “drop-in solution” could enable continuous recycling as PS reportedly does not degrade during the process. In addition, RecyClass has developed guidelines for PS recycling that David Eslava, RecyClass’ PS technical committee chairman and deputy director at Eslava Plasticos, claimed was “pivotal in getting the recycling of polystyrene-based packaging off the ground” at the time.

Similarly, the NEXTLOOPP project is “gather[ing] stakeholders across the PP supply chain” to “create a circular economy for food-grade PP packaging waste”, which it says could reduce fossil-based virgin plastic use, decrease CO2 emissions, and divert waste from incineration and landfill. The companies involved include Danone, Viridor, Sealed Air, Tomra, and Unilever, while a two-year collaboration with INEOS Olefins and Polymers Europe will focus on developing a demonstration plant in the UK with the capacity to produce 10,000 tonnes of food-grade rPP annually.

No comments yet