Picture a bottle of wine in your mind. There’s no question that you imagined it to be contained in a single material: glass. The same can be said for bottled water – most consumers nowadays expect their Evian, Volvic or Vittel to come packaged in PET, or some variant thereof. In fact, it’s hard to think of products that are more intrinsically linked to a certain packaging medium than wine with glass and water with PET.

However, in response to changing consumer attitudes and technological advancements, could the supremacy of these materials for wine and water applications be nearing its end? The fact of the matter is that a new packaging medium for these beverages is starting to gain traction: aluminium cans.

While still occupying a relatively small percentage of their respective markets, canned wines and waters are certainly starting to establish themselves. In the UK for example, consumption of canned wine increased 125% in the year to August 2019 – a trend that is broadly reflected in other territories.

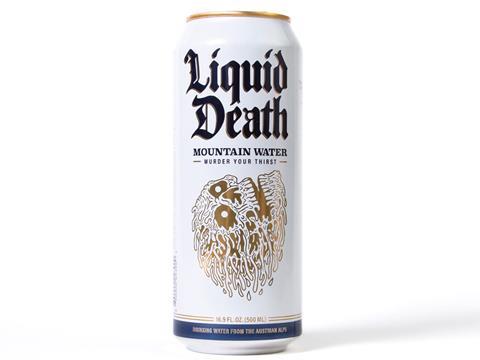

Disruptors such as CanO and Liquid Death are leading the way in the canned water sector, while established, respected wine producers such as Coppola and Barefoot now offer their pino grigios and pinot noirs in canned form. Indeed, Mark Satchwell, managing director of Greencroft Bottling says that “canned wine consumption is growing at a rate of approximately 6% year on year in Western Europe.”

Might beer – a beverage that was once exclusively packaged in glass containers – hold the key to this trend? Despite only being canned for the first time in 1933, canned beer has undeniably become a ubiquitous product. So, can the same be said for wine and water – will canned versions of these products soon become as mainstream as canned beer? And, if this becomes a reality, what implications might this have for the wider industry?

The taste test

Wine producers expend an enormous amount of time and energy on ensuring that their products taste exactly as they should. Then, when the product is ready to consume, sommeliers are paid good money to ascertain the differences between a tannic Malbec and a gentle one. And, while water is commonly believed to “taste of nothing”, factors such as minerality and source do indeed have an effect on its flavour.

This begs the question: does the material in which a beverage is packaged have any effect on its taste?

In an entirely non-scientific test, my colleagues at Packaging Europe and I could detect no distinct differences between a canned variety of Malbec, when compared with a bottled one. Likewise, perhaps unsurprisingly, we were also unable to taste the difference between bottled and canned water. Tests run by WICresearch, an advocacy group, under more scientific conditions appear to have reached similar conclusions. Of the people surveyed, most preferred the bottled wine they tasted – but only by a minuscule margin.

While taste tests like this can be viewed as essentially arbitrary, there are, in fact, a few scientific factors which suggest that canning might aid the flavour of the liquid it is used to contain. Aluminium’s opacity purportedly slows down the rate of sunlight-related oxidation – a phenomenon which can lead to flavour loss. Moreover, due to its chemical qualities, aluminium chills faster than glass and PET – meaning that your craving for cool water on a hot summer’s day will probably be satisfied sooner by a can of Liquid Death than a bottle of Acqua Panna. That being said, one of the key components of a wine’s flavour – age – can apparently be negatively affected by the canning process. In most cases, it is not recommended that consumers age their wine in cans in the same way that they might with a bottle.

However, despite all these conclusions, it’s clear that most consumers (including those at Packaging Europe Towers) are unable to spot the difference.

Design possibilities

We’ve ascertained that there is little (if any) variance between the tastes of canned and bottled liquids. But aluminium canning also presents another point of divergence: shelf-appeal.

When walking down a supermarket beverage aisle, the key design difference between bottles and cans becomes obvious. Most bottles are decorated with a label or sleeve made of paper or plastic, whereas most cans have designs printed directly onto them – usually either digitally or via a more physical process.

Marvin Foreman, sales manager at Tonejet Limited argues that cans are manufactured to a higher precision than their counterparts, meaning that, at least in terms of digital printing, they can be printed onto with greater accuracy. Cans are formed by being drawn out from discs, and, because aluminium is relatively soft and pliable, Foreman says that the same diameter is achieved every time. With a material like glass, for example, the industrial manufacturing process often involves the blowing of molten glass, and Foreman argues that the resulting shrinkage during cooling can result in inconsistent diameters.

This can apparently become a problem during digital printing, a non-contact process that requires the printhead to be mounted at a precise distance away from the bottle. To reduce the risk of collision, “printheads have to be set further away from the bottle surface, which in turn reduces print quality significantly.” As well as similarly being subject to shrinkage, Foreman claims that PET is “inherently flexible and more difficult to move through a printer without deforming the outer surface.”

But, according to Foreman, printing directly onto beverage cans presents issues of its own. Most cans are varnished with a Teflon coating that makes it challenging to get ink to adhere. And, in addition to this coating, the external surface of these cans is often contaminated with fibres, particles, dust and oil. Foreman argues that these features mean that companies like Tonejet are “attempting to print onto a very difficult substrate.”

Resource management

So, our cans have now been manufactured, designed and consumed – but what about end-of-life, and how might increased demand for different applications affect the sustainability of aluminium as a material?

Above all, the aluminium industry prides itself on its strong recycling rate – 74.5% in the EU according to European Aluminium – putting it well above the EU’s Circular Economy Package stipulation of 60% by 2030. Regarding the process itself, David Van Heuverswyn, director of Every Can Counts Europe claims that it takes an average of 60 days – from collection to the redistribution of fully-recycled aluminium coils. Like glass, and unlike PET, aluminium is a permanent product – meaning that it can be recycled countless times without losing its material characteristics.

However, despite aluminium’s positive qualities in terms of recyclability, like other materials, it has its downsides when the full sustainability picture is considered.

Aluminium has impressive recycling rates, but increased demand for aluminium cans for water and wine applications might necessitate the production of more virgin aluminium – a process that, according to European Aluminium’s own figures, uses 95% more energy than the process of recycling the same material. As Van Heuverswyn says, “even if we would recycle 100% of the cans put on the market, as demand is growing further, virgin aluminium has to be used to fulfil said demand.” It’s no secret that this process – mining and refining bauxite ore into aluminium – causes significant damage to the environment through water pollution, deforestation and carbon emissions, when managed irresponsibly.

It’s clear then that the industry as a whole will need to encourage more sustainable practices if it needs to scale up production to meet potential future demand for wine and water applications. The International Aluminium Institute proposes a number of potential solutions to these issues, including the protection of culturally and environmentally significant areas, construction of settling ponds and other drainage control structures, the implementation of rehabilitation measures, and biodiversity management. And according to David Van Heuverswyn, “the collection and sorting of used cans need to be further improved, in order to better facilitate can-to-can recycling”.

The growth of aluminium cans for the purposes of containing water and wine represents true disruption: an innovation that significantly alters an established commercial reality. However, despite the increasing presence of aluminium in this context, glass and PET still occupy the vast majority of the market. And, until cans reach the peak of their potential in this regard, the ultimate impact that this ascendance might have on taste, design, and sustainability habits remains to be seen.