Dr Thomas Reiner, chair of the Deutsches Verpackungsinstitut, CEO of design agency Berndt+ Partner and a member of the judging panel for the 2018 Sustainability Awards, speaks to Elisabeth Skoda about the environmental challenges facing packaging today.

1. Plastic waste: A global solution to a global problem

Figures by the Ellen MacArthur Foundation show that in 2013, around 78 million tons of plastics were used for packaging, 68 per cent of which were collected after use. Fourteen per cent respectively were recycled or incinerated, 40 per cent ended up in landfill. The remaining 32 per cent, however, ended up in nature – an equivalent of almost 25 million tons a year.

A big share of this ends up in the world’s oceans, where it joins other plastic waste, for example from fishery. In total, this amounts to 150 million tons of plastic in the oceans. Even Arctic seawater can contain over 12,000 micro plastic parts, according to research recently published by the Alfred-Wegner-Institut (AWI) in Bremerhaven in Germany.

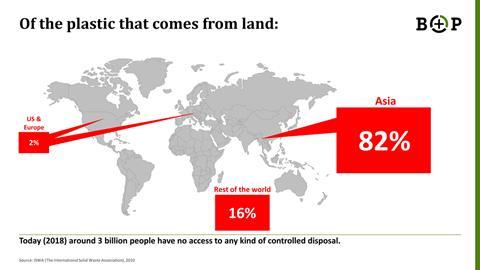

Looking at the sources of used plastic packaging in the environment, 98 per cent of plastic waste in the oceans worldwide comes from countries outside Europe and the US. Between 88 and 95 per cent reach sea via only ten rivers, eight of which are in Asia. The top three are Yangtze, Indus and the Yellow River.

Regardless of regional hotspots for uncontrolled plastic waste, the problem must be solved on a global level. Our commodity flows cover the entire planet just as oceans do. Whoever launches a product on the market should also take responsibility. This is not just a question of ethics, but of economy, offering obligations and opportunities.

A central factor for the solution of this problem are technological solutions and the creation of a suitable infrastructure in the countries concerned, with systems for collection and recycling. Right now, three billion people don’t have any access to such systems. There are projects in place working towards fixing this, but they don’t go far enough. At the same time, it is key to consistently optimise plastic packaging for later recycling.

2. Sustainability does not come for free

The solution of ecological problems requires a lot of effort and costs money. In order to achieve the desired results, we cannot rely on industry and consumers across the world acting responsibly. Past experience shows that existing product alternatives cannot compete on the market without incentives. The business risk associated with the development of alternative solutions poses a real hurdle, as does the buying behaviour of customers, which, contrary to what opinion polls may suggest, hasn’t shown a surge in demand for environmentally friendly products.

Research has shown that sustainable consumerism can only prevail if it is promoted by the state, for example with energy saving home appliances or light bulbs. Let’s accept reality: where it is left to the market whether green products prevail or not, sustainable products never make it beyond niche status.

State regulation can take different forms. Bans are one option, like the ones the EU has introduced for single use cutlery or plastic straws. Another option is taxes, as is being currently discussed for all plastic packaging. A third option uses parameters and quotas for recycling. The German Packaging Act, coming into force on 1 January 2019, stipulates pre-defined quota to reach an increase in recycling from the previously required 36 per cent to 63 per cent in the year 2022. The new EU plastics strategy stipulates that all plastics packaging must be recyclable by 2030. Similar measures are planned for the US, where the American Chemistry Council’s Plastics Division recently published its plans.

Recycling within the framework of a circular economy is the only long term, sustainable solution in order to reduce plastics waste in nature. The EU has recognised this with its new plastics strategy. The necessary collection and recycling systems go together with a value rating system which is bureaucratic and costly but will be a valuable guidance tool. Currently, recycling systems such as ‘Der grüne Punkt’ in Germany only consider the disposal costs of a pack. In the future, recycling properties also have to be considered. Packaging that can easily be recycled receives a bonus, poorly recyclable packaging receives a malus. The European Union has announced a suggestion to such a system for the coming year.

The EU’s plastic strategy has recognised that solving this problem can be a lucrative business model. Investing in innovative, new technologies protects citizens and environment, keeps industry competitive and creates new growth opportunities. The EU plastics strategy was not devised by the EU’s Environmental Bureau alone, but also included business departments. This happened for a reason. According to recent reports, the Chinese share of patents granted worldwide for circular economy technology grew on average by 13 per cent per year between 2010 and 2014.

Due to the fact mentioned above that three billion people don’t have access to controlled waste disposal, we have to export and share our own, innovative systems. Regulation and aid have to go hand in hand, especially in regions where public money is scarce.

3. The supply chain must accept responsibility

Whether or not we will manage to get to grips with the global problem of uncontrolled plastic waste depends on companies within the supply chain who must provide solutions with innovations and by involving consumers. This includes product and packaging manufacturers as well as retail.

Innovations in technology, material and processes are the foundation of the circular economy, creating the necessary possibilities and recycling convenience for consumers. Only solutions that are easy to carry out and that fit seamlessly into peoples’ lives will be successful.

According to a current survey in Germany, almost 60 per cent feel that they’re not sufficiently informed about packaging. Therefore, it is comes as no surprise that packaging in general has a bad image and is wrongly judged with regards to its eco balance. At the same time, over 30 per cent of people surveyed failed to correctly dispose of used packaging, a figure that rose to over 45 per cent in the age group of under 24s.

Retail, product- and packaging manufacturers should provide more and better information. Brands should routinely consider packaging as part of their product and make information about materials, functionality and recyclability more accessible for everybody. Retail should use its strong, direct contact with consumers and push forward innovative collection and recycling solutions.

First and foremost, thinking and acting in closed loops has to be implemented and established as standard. Sustainability is more than disposal, it is key to look at the big picture.

4. Circular economy and closed loops

The currently common distinction of single use and reusable packaging does not go far enough. Each pack should be collected and recycled after consumption.

A good example for how innovative, sustainable solutions can be pushed by the supply chain is the PET bottle. The immediate collection through retail in the shape of deposit return schemes resulted in a particular purity of collected materials, which makes recycling simple and efficient. Even though this is not feasible for all types of packaging, there are plenty of opportunities that are currently not being taken advantage of, for example in the areas of plastic trays and cups.

This also solves the problem mentioned above that solutions should be convenient for the consumer. In times of communicative overload, educating consumers requires a lot of effort. Transparent, closed loops focusing on recyclable materials and automated separation technologies appear to be the most productive solution.

The basis for a successful circular economy remains the practical, efficient recyclability of products.

5. Design for recycling: post-consumption is pre-consumption

In the past, packs were developed according to different criteria. Cost (for purchase and disposal, the total cost of ownership), performance (machinability, barrier, resealability) and environment.

Up until recently, environmental consideration played a small part. Following a short (and very expensive) phase of environmental performance evaluations, some retail brands focus on CO2 and carbon footprint. Experience shows that it is difficult and almost impossible to grasp environmental impact in its totality and use as development criteria for packaging.

In recent years, the discussion focus has shifted from climate change to the waste problem. The ‘Design for Recycling’ principle seizes this point by not focusing on diverse environmental or disposal costs, but recyclability. This gives the topic of packaging sustainability an entirely new drive.

Design for Recycling puts the recyclability of a pack in focus from the very start. Engineers and designers now start development with the end in mind.

Design agency Berndt+Partner has focused on sustainable solutions for ten years, and founder Professor Dieter Berndt was involved in the first packaging directive at the beginning of the 1990s. For us, design for recycling in the context of convenient technological solutions is a key tool for avoiding future problems. Marketers need clear guidelines and evaluation criteria, which is being worked out with the bonus-malus system mentioned above.

Furthermore, recyclates for high value applications have to actually be used. Berndt+Partner is running several pilot projects. In a multi-client study, we examined the use of recyclates for high value packaging applications. The result showed that the issue wasn’t demand from brand owners, but the supply. The recyclate should become a business model for disposal firms, and it absolutely has the potential to do so. Design for Recycling can create or optimise requirements, by securing recyclate quality and quantity.

6. Beyond the circular economy

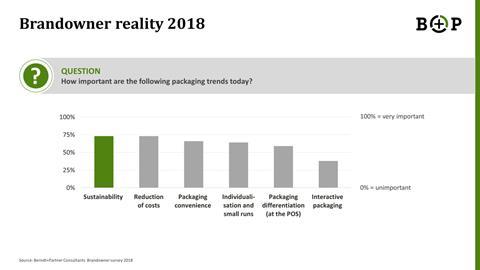

A recent survey of European brand manufacturers showed that sustainability has become a number one trend topic in 2018. It would not go far enough to reduce this mega trend to environmental protection or the circular economy. It involves a lot more, including second or third generation bio plastics and renewable resources in general. Last but not least, we also have to focus on consumer protection.

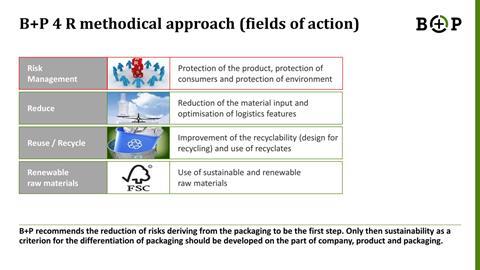

Berndt + Partner therefore adds a fourth R to the classic three (reduce, recycle, renewables): risk reduction. We introduced a traffic light system which reduces material risks and avoid critical substances, even if they aren’t regulated or banned yet. At the same time, we use a sustainability business tool, which means optimising packaging sustainability in all steps of development.