We know that start-ups – in whatever sector they exist – are vital to the growth of an industry. They can provide that vital fresh perspective, developing new solutions to old problems. Netherlands-based Circularise is a case in point: a company that is using emerging cryptographic and blockchain technologies to speed up the transition to a circular economy. In the first of an ongoing series of start-up focused articles, Victoria Hattersley spoke to Jordi de Vos, one of the company’s founders, about how this can be achieved and the particular challenges it has faced as a new entrant to the market.

How can we achieve a circular economy? It’s a question we’ve asked again and again, in many contexts, and there is no single answer. Perhaps a better question to ask might be, what are the barriers and how can each be overcome?

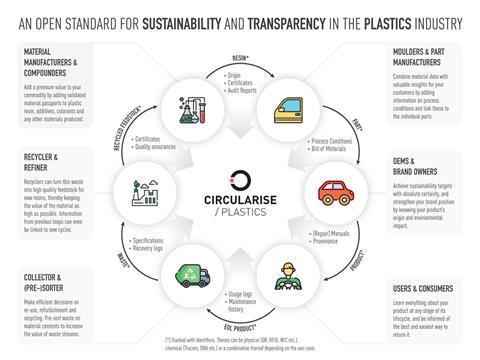

One of the biggest of these is the inability of each member along the supply chain to track the provenance of all materials, products and components from production to end-of-line. So many of the people we have spoken to over the years have talked about the importance of greater collaboration throughout the packaging value chain to reduce carbon footprints, cut waste and generally create the most sustainable solutions.

But maybe a possible solution to this is appearing on the horizon. Netherlands-based start-up Circularise is developing a protocol that utilizes a combination of blockchain, peer-to-peer technology and cryptographic techniques to build a decentralized information storage and communication platform. Along with project partners DOMO and Covestro it is working on the implementation of this solution in the plastics sector.

‘A lack of information’

Up to now, many may be more familiar with blockchain in relation to cryptocurrency, and if they associate it with the packaging industry at all it tends to be more in the context of anti-counterfeiting.

So in brief, for those (like myself, I freely add) who are not experts on the subject, blockchain is essentially a series of data records or ‘blocks’ managed by a cluster of computers or ‘nodes’. Crucially, they are not run by a central authority, which some would say makes this a far more democratic system – one that is open to building greater transparency along the supply chain.

What makes Circularise’s protocol particularly significant? (After all, it is by no means the only one to employ blockchain.) In a (hyphenated) word: knowledge-sharing. The first main element of the Circularise blockchain solution involves the creation of a single digital replica of the customer’s real-world product or material, elements of which can be shared at their own discretion.

“Right now, if we look at the recycling loop, it’s not very effective because there’s a lack of information,” explains Jordi de Vos. “Imagine all the different kinds of packaging, particularly the different plastics and combinations of these, and how difficult this makes it for recyclers to market the most optimal choice. If we can provide them with the information they need from somewhere in the supply chain it means they can ultimately get a more high-quality resource from their waste. After all, while there is a lot of plastic waste, plastic itself is not the real problem as it’s a great material that if used correctly would be better than a lot of the alternatives. But the problem is we’re not using it correctly now.”

And he argues that, while there is certainly a lot of work going on in the blockchain space, so far it seems there has been relatively little attention paid to its possible role in the plastics supply chain. Furthermore, when we do see this happening it is generally based on a single party or a consortium, whereas Circularise “tries to be for the industry as a whole.”

When it comes to plastics, he says the protocol could bring two big potential gains. At the recycling stage, companies would be able to make better choices and bring single-use plastics to multi-use without having to change their business model.

The second benefit is more practical. “For example, where I live we have a lot of garbage bins and it is difficult to know what to throw in each one, which could lead to contamination of the whole batch. The idea is that if you can uniquely identify all the separate elements of the process we can automate the sorting part that the customer now does – so they’d just throw everything in the same bin and let the robot do it in the sorting facility.”

The security question – enter Zero Knowledge Proofs

But there’s a caveat to all the potential benefits of the blockchain approach (when is there not?): when it comes to knowledge-sharing along the supply chain, there are always going to be security and confidentiality concerns. As it is still a relatively new technology, some companies are naturally wary of blockchain. Does it really, they would ask, provide the data security so vital to ensuring brand protection?

“I think the push for greater transparency has been out there for at least 20 years and is getting more and more important as public opinion changes,” says Mr de Vos. “But up to now we have never had the technology that would have allowed all these parties to work together without risking all their IP and sensitive information. For them, more transparency can be a risk but with the technology we are developing they can afford to do this.” If true, this is clearly exciting because it could be one of pieces of the complex puzzle that needs to be solved on the road to circularity.

This is where the second key element of the Circularise protocol comes into play: Zero Knowledge Proofs (ZKP). This is a cryptographic technique that allows the user to keep data secret (even from Circularise itself), while sharing certain parts of their solution. In this way they can pass on insights that may be vital to the efficiency of the supply chain without sharing everything.

To give an example of how this protocol might work: say a plastic contains some fire-retardant additives. Maybe the producer doesn’t want to share their entire recipe, for obvious security reasons, but it’s important for those further down the supply chain (sorters, recyclers, etc.) to know what this particular additive is so they can make the right end-of-line decision. Using the ZKP is a way to share knowledge and prove the data is correct without disclosing it all. A win-win for everyone, perhaps?

“Yes, some might argue there are other ways to do this – encryption, for example – but assuming that technology keeps moving forward the way it has been there will be a time when that encryption can be broken. Let’s use the example of a soft drinks company which has a secret recipe – this information can’t be changed like a password because it’s fixed, which means it could be vulnerable if encrypted. In this scenario, it is better to use ZKP.”

Challenges, past and future

All of this sounds promising, but of course we can only really judge its potential impact when full-scale commercialisation takes place – something which is imminent. The first version of the Circularise protocol tailored specifically to the plastics industry has been developed, and was demonstrated at CES 2020 in Las Vegas in early January. To begin with it will be focused on other kinds of plastic than packaging, but the system is also prepared for that and the company expects it to be ready for mass market release at the end of 2020.

As with any new solution, there have been a plethora of challenges along the road to get it to this point; and it doesn’t end with commercialisation – there will likely be more barriers to leap.

“I guess the biggest challenge is the speed of corporates (or lack thereof!). Plastics is a very traditional industry that is slow to make changes, whereas we as a start-up are compelled to move fast.

“I think another problem is that, when we’ve talked to stakeholders across the supply chain, many agree our protocol would add value for their customers, but wonder how they can capture it for themselves. There are still a lot of questions that need to be answered, but we’re getting there.”

Then, of course, there is always the spectre of legislative hurdles hovering over any disruptive innovation. “We don’t need more legislation within the plastics industry, although standardisation would be beneficial. Up to now we have been completely supported by the EC, but I would rather see change happening from within the industry itself or we may start to become bogged down by rules.”

There are certainly suggestions that there’s a way to go before this technology is fully embraced. The recent CB Insights report, ‘Blockchain Trends in Review’, says that VC capital in the space has seriously declined in 2019: only $1.6 billion invested across 454 deals, down from the $4.1 billion invested the previous year.

But on the positive side, it seems there is increasing recognition of blockchain from within the industrial space – it is no longer reserved for the fintech sector. According to the Deloitte 2019 Global Blockchain Survey, 53% of senior executives surveyed said that blockchain would be in their top five strategic priorities – a 10-point increase over the previous year. And even the CB Insights report does point out that recent corporate interest could be a ‘good omen’ for blockchain start-ups as the specific knowledge of blockchain can rarely be found in-house and will be needed as the space institutionalizes.

Mr de Vos confirms this: “To be honest, the parties we work with are capable of developing their own IT solutions like this in-house. But this brings with it a lot of internal risks, and then of course they are just building it for themselves which doesn’t help the industry as a whole. That’s why a start-up, standing between these parties and serving the entire supply chain, can be way more effective.”

“What it comes down to is the big corporates recognising that start-ups play a very specific role in their innovation challenges and the more they realise this the faster they can update themselves and still remain ahead of the curve.”

‘Helping to shape the conversation’

On the subject of change from within the industry, let’s briefly go back to the above-mentioned challenge facing start-ups; specifically, the slow pace of corporates in long-established industries vs. the speed required for a start-up to get off the ground. Is this a common tension for new companies, regardless of their specialization?

“Yes, I would say so,” say Jordi de Vos. “Start-ups have to prove things quickly if they are to succeed. But even negotiating a contract with large players can take months, which for a company like ours is not good. That’s why as a start-up you are obliged to be selective about who you do business with in the beginning.”

We’re also interested to know his views on the kind of support available to young companies seeking to have a disruptive effect. Is it sufficient, or does industry need new models to address this?

“We are basically seeing a big gap in funding and support, from ideas to execution to new venture partners. That’s what we describe as the ‘value gap’ for start-ups. Investors are coming in at later and later stages and want to see more security and more recurring revenue before they commit, which is a problem. I hope that in the future corporates will come together and try to fill the gap in investment. If this happened, I think we would begin to see a lot more innovation happening.”

Fresh voices are increasingly helping to shape the conversation around sustainability. By nature, says Mr de Vos, they can be more disruptive because they have less ‘baggage’ to carry and long-standing clients to please.

And blockchain is just one of the building blocks of a circular economy. In the coming months we will be hearing from a range of other start-ups from different segments of the packaging industry, to get a clearer picture of the specific challenges they face and how they feel innovation can be better nurtured.

One thing we are sure of: while the long-term experience of the big corporates is of course invaluable, getting a new, ‘younger’ perspective on the global environmental problems we all face is vital – whether that’s from industry, politics or grassroots activism. (As the glowing example of Greta Thunberg, for one, has shown us.)