Marco Mensink, director general of the Confederation of European Paper Industries (CEPI), talks to Tim Sykes about developing the breakthrough technologies that will enable the paper industry to hit carbon reduction targets while remaining economical.

Tim Sykes:

CEPI’s Forest Fibre Industry 2050 Roadmap poses the question of how to achieve 80 per cent reductions in fossil-based CO2 emissions while creating 50 per cent more added value. In what context were these targets set?

Marco Mensink:

In March 2011, the European Commission published the EU ‘Roadmap for moving to a competitive low-carbon economy in 2050’, a discussion document to explore the future of climate change policy. The CEPI roadmap attempts to lay out the future of the forest fibre industry and its potential to meet emission reduction in line with the modelled overall industrial reduction of 80 per cent by 2050, compared to 1990 levels.

It is the start of a wider debate and has grown into a platform for the industry to discuss the future. We have clearly built upon the European Commission’s document and our Roadmap has been embraced to the extent that we have already distributed 7000 copies and several print reruns. It has been present on every management table throughout the industry within the last two years.

The CEPI Roadmap concluded that the breakthrough technologies the industry needs in order to meet an emission reduction of 80 per cent by 2050 are not available today. To achieve an 80 per cent CO2 reduction, breakthrough technologies would need to be developed and available by 2030. 2050 is two paper machines away, meaning two investment cycles maximum. A reduction of 50 per cent CO2 by 2050 is possible in the right circumstances, however the industry needs to be able to invest to make the changes and meet the targets.

Tim Sykes:

What are the implications for the paper industry if the targets are not met?

Marco Mensink:

There are a lot of ‘ifs’ depending on the predictions of the European Commission. Of course, no one predicted the economic crisis, and no one is certain what the future European economy will look like. We clearly included the targets as a goal to work towards but also acknowledge that these are based on a reality that might or might not be in the future.

However, it is clear that the climate change agreement is still moving forward. The European Commission just set a minus 40 per cent emission reduction target by 2030 in-line with its aim to achieve a minus 80 per cent target by 2050. It is clear to us that if the rest of the world does not come along, the second part of this period will see very heavy debates in the developments between the competitiveness of European industry vis-à-vis global obligations.

What happens if we do not manage our energy intensiveness over the years? There is awareness within the industry that if we do not tackle our energy intensity, we will face an uphill battle for years to come. We will become uncompetitive with regards to cost compared to other materials, or other regions in the world. There is no clear penalty yet, but the carbon cost and the energy cost will increase, and in order to stay in business we need to improve. The industry needs to use technologies that will not only decarbonise, but also add value or reduce costs.

Tim Sykes:

One of the conclusions CEPI reached was that breakthrough technologies would be needed by 2030 in order to achieve the targets. Are you able to quantify the gap between gains we expect to make through resource/energy/conversion efficiency and the 80 per cent target, which must be bridged by new technologies?

Marco Mensink:

An important point we have made to the policy makers is that they have to understand the way investments work in this sector. In the past, policy never really considered how investment cycles in the industry work. The investment into a paper machine will be there for 20 to 30 years. So efficiency can indeed improve over the years but the major share of the energy consumption is pretty much fixed from the moment the machine is bought.

The old equipment of today will either be out of business or replaced by 2050 and as long as industry keeps investing in Europe by upgrading and replacing; efficiency will improve. The same will happen through ongoing consolidation.

You can already see the efforts we are taking as we have reduced absolute emissions by 22 per cent since 2005. This is partly due to a shift towards the use of biomass, or of combined heat and power. The fuel mix used now is slightly more than half biomass based, 40 per cent natural gas and CHP, four per cent oil and four per cent coal. That is around the limit you can now reach in Europe for fuel efficiency.

The next step to be taken is that the electricity grids should also be decarbonised. Then there is still the breakthrough technology gap left which needs to bring the difference from the minus 50 to the minus 80 reduction. For some of these technologies, if they were implemented throughout the entire sector you would see possible carbon reductions of 20% and energy reductions of 40%.

Tim Sykes:

CEPI organised the Two Team Project as a means to identify areas where breakthrough technologies could be developed. Why the concept of two competing teams and where did they look for inspiration?

Marco Mensink:

We thought that with only one group investigating, we would end up with something like a consultant’s report. We were looking for a way to keep up the enthusiasm in the sector and to get the best ideas out. Two competing teams was a new concept to the process and a way to challenge people. Both were unaware of each other’s activities until after the jury’s decision.

Paper producers, suppliers, customers, and complete outsiders were spread between the teams and we specifically broke existing links between them to encourage the competition. We held our meetings in unusual places such as in Atomium in Brussels. This added to the success of the project and raised awareness.

The teams were left to develop their own ideas, on the condition that they delivered their concepts (not specific technologies) within a year to the jury and demonstrated a broad idea of how to turn the sector around. They were asked to investigate both the value and carbon reduction, and to quantify the results in the same manner as the other team.

The logical step was to look at technologies that can alter the papermaking process, which is where the biggest loss of energy through water evaporation occurs, and the biggest use of energy occurs through the pulping process (either by cooking or grinding).

Tim Sykes:

Could you tell me about some of the most interesting concepts that were generated from the project?

Marco Mensink:

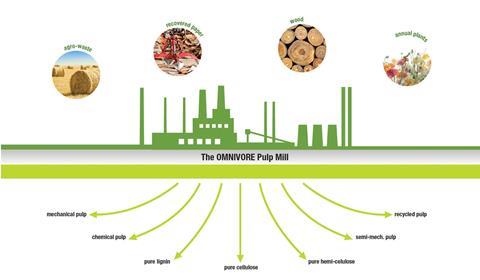

Many of the approaches looked at how natural or technological processes distinct from our industry could be applied to paper making. The first concept is using Deep Eutectic Solvents, which are produced by plants to protect against water stress. We tracked down a professor who was studying this and she explained that DES could dissolve biomass at room temperature into lignin, cellulose and hemicellulose in half an hour. This came as quite a shock to the industry, raising the prospect of significant energy savings in the pulping process.

The technology is already operating at a laboratory scale and the promise is such that 17 companies have formed a consortium. All the big industry players have come together for the first time in history to pay for two PhD students to develop this further. It is a completely new breakthrough pulping technology using biomass. Mimicking nature has the potential to take out 40 per cent of the energy consumption of the sector.

A second concept looked at DryPulp for cureformed paper. Here we again looked at mimicking nature. When Penguins swim, air-bubbles are formed on their feathers, reducing friction in the water and speeding them up. The Russians copied this concept for their torpedoes and Boeing applied it to its Dreamliner. In papermaking bio-based substances could be used to modify the viscosity around fibres. Combined with cureforming, which allows the formation of a thin sheet, it is possible to produce the sheet as a layered product, in response to demand for certain properties and with the means to add new functionalities, while drastically reducing the amount of water needed.

A third concept is Supercritical CO2, which is neither liquid nor gas. This is used in the decaffeinating coffee process and also by clothes manufacturers, where liquid C02 is used to dye fabrics – and to dry them as it evaporates. This is another technology that eliminates water and it can be applied to paper production as a means to dry pulp and paper without the need for heat and steam, as well as dyeing paper and removing contaminants in the same process.

Tim Sykes:

Some great ideas emerged from this project. How does the industry and society as a whole make sure further R&D takes place with the necessary investment behind it? What has happened in the 12 months since the teams reported back?

Marco Mensink:

CEPI ended up owning patent applications. We were able to publish our findings and we licensed out all the rights. We built consortia around most of the concepts, either through carrying out research or developing projects for co-funding by governments.

The transformation process over the next fifteen years is something we are looking into. It could be very small companies coming in and pushing big companies off the market or very big companies owning the technology and not allowing small ones to compete on the market due to capital cost. All of those processes will determine which technology will win in the end and we think we will see a mix where not all of the eight winning concepts will make it to the finish line. It will ultimately be the market that decides.

We have taken the next step by developing the consortia and at CEPI we are focusing on innovation policy and how governments can support projects. In the past Europe was very good at supporting research, but when it comes to developing pilots and demonstration plants, these tend to be invested in elsewhere, such as the US.

The role of CEPI now since the Two Team Project is to help create funding opportunities and keep these technologies in Europe. Alongside other sectors, the Biobased Industries Consortium has been built to develop pilots, demos and flagships. It is worth 3.8 billion euros (one billion euros paid by the European commission). This is a big step forward and we are now looking to the next round of funding for after 2020 to continue the development of these ideas.

The risk to a company to be the first one using a completely new technology is enormous. Which company wants to take that risk? There is a good example in the steel industry which has also developed breakthrough technology. One of those technologies is at Tata Steel in the Netherlands. The big question is will it be developed here in Europe or in India where there are growing markets.

The biggest hurdle for the industry in Europe is to safeguard and ensure breakthrough technologies are developed here on European soil. To ensure this we need to work very closely together with governments and continue to look into EU innovation policy and national innovation policy.

Tim Sykes:

Apart from the particular technologies the teams considered, did they come to any conclusions about changing the industry’s approach?

Marco Mensink:

In the packaging industry corrugated board is bought by the square metre, whereas paper is bought by the tonne. If you look at the technology of lightweighting as an example, when you make the paper lighter it is beneficial for the environment, however the specific energy consumption per tonne increases.

So in this case, if you calculate in tonnes only, you cannot see the benefits of the innovation. Therefore, perhaps tonnes are not the best measurement. Selling by the square metres and according to functionalities may be more appropriate. In the end the paper industry should not be producing tonnes, we should produce value.