As fibre-based materials innovate to increasingly compete in packaging niches recently dominates by plastics, brand owners face new challenges in evaluating respective sustainability implications. Tim Sykes spoke to Smurfit Kappa’s Arco Berkenbosch (VP innovation and development) and Jurgita Girzadiene (sustainability manager) about novel corrugated applications, a new approach to lifecycle analysis, and carbon footprints.

At Packaging Europe we’re pushing the climate crisis to the top of the sustainability agenda – and many of the most fundamental and contentious questions the packaging world must face lie at the intersection of carbon footprint and circularity. While the plastics value chain works on design for recyclability and building a viable circular economy, the paper industry is exploring opportunities to provide already recyclable alternatives to plastic packaging applications. Indeed, recent research has estimated that in European supermarkets 1.5 million tonnes of plastic could be replaced annually. As paper and plastics come to compete across more packaging contexts, brand owners will have decisions to make. As plastics raise their recyclability and paper innovates around functionality, how do brand owners assess the relative sustainability credentials?

Creating alternatives to certain plastic applications – particularly around aggregation – has been on Smurfit Kappa’s strategic agenda for some time. At one end of the scale this has involved resurrecting traditional formats (such as corrugated trays and punnets) which had over the years been displaced by flexibles. At the other there has been blue-sky thinking: the company’s inaugural Better Planet Packaging design challenge brief asked designers to create paper-based alternatives to flexible pallet wrap. In between these poles, its R&D teams have been developing innovative products such as TopClip (an alternative to shrink film for can aggregation) and GreenClip (a replacement for plastic rings). TopClip, which utilises no glue and according to Smurfit Kappa boasts higher recycled content and lower carbon footprint than competing solutions, is already being trialled on shelves. Further collaborative projects with brand owners are set to be announced over the course of 2020.

But as all segments of the industry progress around offering recyclable solutions, what are the relative carbon footprints, and how do we form a holistic view of the respective impacts of plastic and paper-based solutions?

Re-evaluating Lifecycle Analysis

As Arco Berkenbosch reveals, Smurfit Kappa has been exploring how LCA can illuminate these dilemmas. In our discussion he began by highlighting the limitations and challenges of benchmarking.

“LCAs are only really useful in looking case by case at specific products,” he said. “With so many variables, you can’t use them to make sweeping generalisations about different materials.”

In addition to the susceptibility of LCAs to be framed for commercial or political reasons by manipulating their initial assumptions and the challenges around acquiring reliable benchmarking data, there’s a basic question of how to make sense of the findings. “Today the focus is often on two key metrics – litter and carbon footprint – and you can’t simply add them together to create an overall ‘sustainability’ number,” Arco remarked. “Nor can we choose one over the other: we have to tackle both problems.”

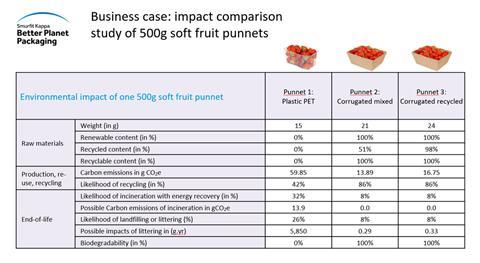

Smurfit Kappa’s innovation here has been to distil LCA data (produced by a third party) into a nuanced snapshot of carbon and end of life metrics relating to a given product from cradle to grave, through its journey from raw material through production and use to end of life. The overview consists of ten metrics, and perhaps the most noteworthy aspect is that the inherent characteristics of the products (such as weight, recycled content, carbon footprint) are set against the real world probability of specified end of life outcomes (recycling, entering the environment, incineration).

For instance, the LCA we look at – comparing fruit punnets made from PET, recycled corrugated and mixed virgin/recycled corrugated – calculates the relative impacts of littering based on gram-years, or g.yr. As Jurgita Girzadiene explained: “This is a metric that has emerged from academia: it reflects the combined impacts of the volume of material entering the natural environment (based on product weight and probability of littering or landfilling) multiplied by the length of time it stays in the environment.” In this case, plastic fares worse, because it’s both less likely to be recycled and takes much longer to break down.

But what of the carbon footprints? In the case of punnets, according to this LCA, the corrugated alternatives come out as comfortable winners. Where the PET punnet creates emissions of nearly 60 g CO2e, the mixed corrugated one is just under 14 g CO2e. Although paper making is quite energy intensive, paper mills are the biggest industrial user of carbon-neutral biomass energy (which is why the recycled corrugated punnet has a slightly higher carbon footprint, at 16.75 g CO2e, than the mixed virgin / recycled one).

Meanwhile, the LCA format records possible carbon emissions through incineration as a separate metric, since energy gained could be offset against the emissions.

So does this settle the plastic vs paper carbon question? As Arco Berkenbosch said at the beginning, it’s not that simple. “This carbon advantage is reduced where plastic is considerably lighter than the corrugated alternative,” he said. “With the fruit punnets the weights are quite similar. However, when you compare shrink film with corrugated replacement, the corrugated is heavier by a factor of five. We’ve just looked at an example in which a corrugated punnet compares very favourably with a PET one, but I could also pick examples where corrugated doesn’t come out so well.”

Smurfit Kappa also acknowledges certain caveats apply to these calculations. While it uses its own real life data, based on a specific mill for corrugated, the LCA relies on third party data that may be more generalised for plastic products. It does not, for instance, attempt to compare the average distances plastic and corrugated products may travel through the entirety of their supply chains. On the other hand, it also doesn’t factor in the carbon storage function of trees – otherwise the carbon footprint of corrugated would come out below zero.

“We will continue to work on our data and assumptions,” Arco Berkenbosch commented. “However, we have found that this is a useful tool to steer conversations with customers facing those strategic sustainability dilemmas. The goal is to help them to make a sensible business decision based on the entirety of the information.”