Sustainability has always been a key factor in plastic packaging design and new techniques are now ensuring it is even more at the heart of the process, explains Brian Lodge, RPC design manager.

From paint to motor oil, fabric conditioner to lawn feed, rigid plastic packaging has long been established as the most appropriate packaging solution for a huge variety of non-food markets. Everyone has benefited from the consumer convenience, strength, light weight and functionality that a well-designed pack can deliver. Nevertheless, recent press campaigns against the use of plastics have brought home to a wider audience an issue that the industry has been addressing for many years - that of designing and manufacturing packs that continue to deliver these many advantages without costing the earth.

Somewhat ironically, one of the many criticisms currently being directed at plastics – the myriad different polymers available – remains a critical reason why plastic is able to meet the differing packaging requirements of so many different products. More significantly, the wise use of available polymers remains the key to creating a sustainable and affordable (both in terms of cost and environmental impact) packaging system.

To achieve this, the starting point has to be the need for a wider understanding of the issues involved, and this can be realised in several ways. At RPC Design, for example, our recent activities have included a visit to a plastics recycling facility and attending a seminar at the House of Lords, as well as a longer term project being involved with the Ellen McArthur foundation to develop circular design tools for designers.

Certainly this is the future for packaging design, to which the traditional parameters of form, function and cost must now be added a pack’s ‘circularity’ as an equally important aspect. This is something that RPC has already begun to implement, modifying our design process to include self-developed tools and also adapting our use of software and facilities to ensure we are creating great packaging that meets all of these requirements.

Approaches to the three Rs – ‘reduce, reuse, recycle’ – of the Circular Economy are very different. To ‘reduce’ we test our designs using FEA (finite element analysis) software as well as things like mould-flow. This allows us to minimise the amount of material we use to create the strength needed to function properly.

Again, this is not a new concept. Packaging designers and manufacturers have long worked on lightweighting techniques, for commercial as well as environmental reasons. As long as four years ago, for example, RPC introduced the world’s first UN approved free-standing five-litre jerrycan for the transportation of hazardous products, weighing just 130g compared to more typical examples of around 200g. More recently, we redesigned a highly complex pack for the horticulture sector, reducing the number of components in the pack by over 50 per cent for an overall weight reduction of 40 per cent.

Both these examples highlight the crucial relationship between functionality and sustainability. A pack has above all to remain fit-for-purpose – if it cannot deliver on its primary purpose, any environmental benefits are worthless.

For this reason ‘reuse’ can be trickier for many industrial applications where the original contents of the container preclude this or the need for tamper-evident seals (essential for many products and often required by law) make reuse difficult. However, there are plenty of examples of pots with pens in and jars containing screws or nails in both commercial and domestic life.

For many plastic pack designs, the main target remains to ‘recycle’ and here designers can have a very big impact by creating packaging that is fully recyclable and which can incorporate post-consumer recycled materials. Using single material packs in PET, PP or HDPE is the first objective, and if this is difficult then making the components easily separable is important. Like lightweighting, the incorporation of PCR requires great technical skill to ensure pack performance and functionality are not compromised in any way, and there are many instances where this has been successfully achieved, such as paint containers with 25 per cent PCR, and oil bottles and tester pots which are 100 per cent PCR.

At RPC we have also developed two bespoke tools to help the design-for-recycling process. The first is our 'Circular Economy Check Sheet', which poses questions for each step of the design process. This requires each designer to challenge the brief, the concepts generated and the final design with a set of questions that ensure we have explored every possibility for making the pack suitable for the CE.

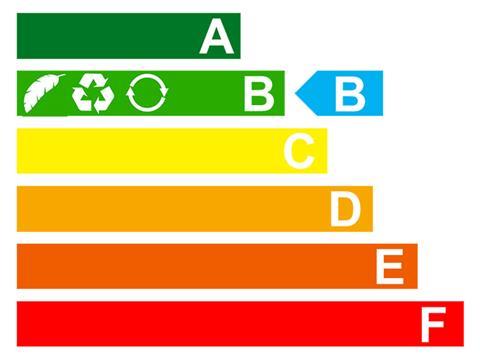

By far the most effective tool has been our recent introduction of a circular grading system that rates each design concept against the Recyclas recyclability scheme. We add to our presentations a pictogram similar to that for energy efficiency used on electric appliances or double glazed windows. Each design has an A to F rating and the coloured bar graph quickly shows the effect of design decisions on its recyclability. We also incorporate symbols to show if it is lightweighted, reusable or made from PCR materials.

Designing for the circular economy does not mean having to throw away all the benefits that well-designed plastic packaging already offers. By applying the right skill and knowledge and using the right tools, it is possible to create packs that fulfil consumer, filler, brand owner and recycler needs without compromise. And that has to be the best way to achieve the more sustainable world that everyone is seeking.